May 2022 Issue

ISSN 2689-291X

ISSN 2689-291X

Pericardial Calcification:

Armored Heart Sign Of Constrictive Pericarditis!

Description

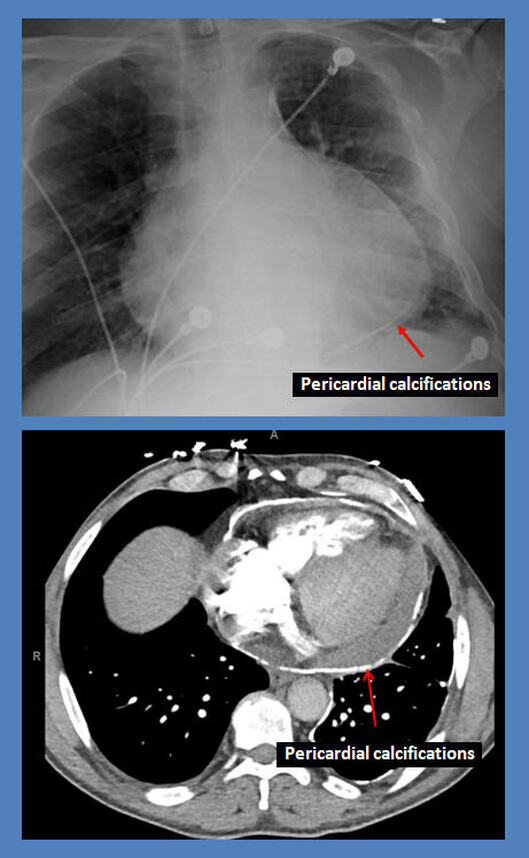

The above posteroanterior chest X ray and coronal computed tomography images reveal, in addition to cardiac enlargement, extensive circumferential pericardial calcifications encasing the entire epicardial surface. Further echocardiographic and invasive hemodynamic studies revealed a combination of restrictive and constrictive cardiomyopathy as a cause of dyspnea, prompting intensive medical treatment given multiple comorbidities and high risk of surgery.

Discussion

In the setting of congestive heart failure, circumferential pericardial calcification outlining the heart border on chest x-ray (known as Panzerherz, or the “Armoured Heart Sign”) is strongly suggestive of calcific constrictive pericarditis [1]. Based on the patient’s presentation and concomitant clinical data, restrictive cardiomyopathy and myocardial calcification and/or scarring (possibly from prior myocardial infarction) can have a similar presentation and will need to be ruled out [2].

Pericardial calcifications can be due to any condition causing chronic pericardial inflammation, and can be an incidental finding without symptoms [3]. Many of the constrictive pericarditis cases are also associated with pericardial calcifications, which tends to have certain circumferential characteristics leading to altered hemodynamics and symptoms [4, 5]. The extent of the calcification is also variable and may contribute to the presence and extent of physiologic changes and symptoms [6].

Some inflammatory conditions leading to pericardial calcifications include infections (tuberculosis, coxsackie B virus, histoplasmosis), penetrating trauma/cardiac injury, cardiac surgery (valve surgery, coronary artery bypass grafting), intrathoracic malignancy (lung and breast cancers, Hodgkin lymphoma, mesothelioma, thymoma, metastases), radiation exposure, uremia, and dialysis [7]. Other potential causes of pericardial calcifications include connective tissue disorders (sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, systemic sclerosis/CREST syndrome), hypothyroidism/ myxedema, hypercholesterolemia, and various drugs/toxins. However, pericardial calcifications can also be idiopathic.

In developed countries, idiopathic constrictive pericarditis is most common, followed by postoperative and post-radiation etiologies [8]. In developing countries, on the other hand, infectious etiologies (especially tuberculosis) remain common. The presence of pericardial calcifications has been linked to increase perioperative mortality during pericardiectomy, which is the curative treatment for symptomatic constrictive pericarditis. Poorer outcomes have also been associated with pericarditis secondary to radiation exposure [9]. This increased perioperative mortality may be related to subepicardial or myocardial involvement of the fibrocalcific process, which can worsen the prognosis and reduce the chances of a successful pericardiectomy [10, 11].

References

Authors:

Shrikar Iragavarapu, B.S.

Medical Student

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Rajasekhar Mulyala, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Maulikkumar Patel, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Usman Sarwar, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Nikky Bardia, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Nupur Shah, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

G. Mustafa Awan, M.D.

Professor of Cardiology

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Christopher Malozzi, D.O.

Associate Professor of Cardiology

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Bassam Omar, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Cardiology

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

The above posteroanterior chest X ray and coronal computed tomography images reveal, in addition to cardiac enlargement, extensive circumferential pericardial calcifications encasing the entire epicardial surface. Further echocardiographic and invasive hemodynamic studies revealed a combination of restrictive and constrictive cardiomyopathy as a cause of dyspnea, prompting intensive medical treatment given multiple comorbidities and high risk of surgery.

Discussion

In the setting of congestive heart failure, circumferential pericardial calcification outlining the heart border on chest x-ray (known as Panzerherz, or the “Armoured Heart Sign”) is strongly suggestive of calcific constrictive pericarditis [1]. Based on the patient’s presentation and concomitant clinical data, restrictive cardiomyopathy and myocardial calcification and/or scarring (possibly from prior myocardial infarction) can have a similar presentation and will need to be ruled out [2].

Pericardial calcifications can be due to any condition causing chronic pericardial inflammation, and can be an incidental finding without symptoms [3]. Many of the constrictive pericarditis cases are also associated with pericardial calcifications, which tends to have certain circumferential characteristics leading to altered hemodynamics and symptoms [4, 5]. The extent of the calcification is also variable and may contribute to the presence and extent of physiologic changes and symptoms [6].

Some inflammatory conditions leading to pericardial calcifications include infections (tuberculosis, coxsackie B virus, histoplasmosis), penetrating trauma/cardiac injury, cardiac surgery (valve surgery, coronary artery bypass grafting), intrathoracic malignancy (lung and breast cancers, Hodgkin lymphoma, mesothelioma, thymoma, metastases), radiation exposure, uremia, and dialysis [7]. Other potential causes of pericardial calcifications include connective tissue disorders (sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, systemic sclerosis/CREST syndrome), hypothyroidism/ myxedema, hypercholesterolemia, and various drugs/toxins. However, pericardial calcifications can also be idiopathic.

In developed countries, idiopathic constrictive pericarditis is most common, followed by postoperative and post-radiation etiologies [8]. In developing countries, on the other hand, infectious etiologies (especially tuberculosis) remain common. The presence of pericardial calcifications has been linked to increase perioperative mortality during pericardiectomy, which is the curative treatment for symptomatic constrictive pericarditis. Poorer outcomes have also been associated with pericarditis secondary to radiation exposure [9]. This increased perioperative mortality may be related to subepicardial or myocardial involvement of the fibrocalcific process, which can worsen the prognosis and reduce the chances of a successful pericardiectomy [10, 11].

References

- Melissa YY Moey, Saleen Khan, Pradeep Arumugham, Constantin Bogdan Marcu. Panzerhertz (Armoured Heart): Case of Idiopathic Severe Calcific Conctrictive Pericarditis. JACC March 8, 2022 Volume 79, Issue 9, suppl A. 3436.

- Khalid N, Hussain K, Shlofmitz E. Pericardial Calcification. 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–.

- Nguyen T, Phillips C, Movahed A. Incidental findings of pericardial calcification. World J Clin Cases. 2014 Sep 16;2(9):455-8.

- Senapati A, Isma'eel HA, Kumar A, Ayache A, Ala CK, Phelan D, Schoenhagen P, Johnston D, Klein AL. Disparity in spatial distribution of pericardial calcifications in constrictive pericarditis. Open Heart. 2018 Oct 7;5(2):e000835.

- Lee MS, Choi JH, Kim YU, Kim SW. Ring-shaped calcific constrictive pericarditis strangling the heart: a case report. Int J Emerg Med. 2014 Sep 30;7:40.

- Zaimi MA, Mamat AZ, Ghazali MZ, Zakaria AD, Sahid NA, Hayati F. Trapped heart in heavily calcified pericardium. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2020 Oct 23;2020(10):omaa083.

- Srinivasan N, Gupta R, Garrison M, Blevins S. Heart in a hard cage: startling calcific constrictive pericarditis. Congest Heart Fail. 2008 May-Jun;14(3):161-3.

- George TJ, Arnaoutakis GJ, Beaty CA, Kilic A, Baumgartner WA, Conte JV. Contemporary etiologies, risk factors, and outcomes after pericardiectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012 Aug;94(2):445-51.

- Ling LH, Oh JK, Breen JF, Schaff HV, Danielson GK, Mahoney DW, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Calcific constrictive pericarditis: is it still with us? Ann Intern Med. 2000 Mar 21;132(6):444-50.

- Bogaert J, Francone M. Pericardial disease: value of CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 2013 May;267(2):340-56.

- Bogaert J, Meyns B, Dymarkowski S, Sinnaeve P, Meuris B. Calcified Constrictive Pericarditis: Prevalence, Distribution Patterns, and Relationship to the Myocardium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Aug;9(8):1013-4.

Authors:

Shrikar Iragavarapu, B.S.

Medical Student

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Rajasekhar Mulyala, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Maulikkumar Patel, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Usman Sarwar, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Nikky Bardia, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Nupur Shah, M.D.

Cardiology Fellow

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

G. Mustafa Awan, M.D.

Professor of Cardiology

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Christopher Malozzi, D.O.

Associate Professor of Cardiology

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

Bassam Omar, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Cardiology

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL